Is the Campaign for Real Ale about to have its Clause Four moment? For younger readers, Clause Four was the part of the constitution of the Labour Party that contained the aim of achieving “the common ownership of the means of production”, and it was when Tony Blair, Labour’s new party leader, and his allies managed to get that dumped in the dustbin of discarded socialist rhetoric in 1995 that New Labour was born. Traditionalists saw the policy celebrated in Clause Four, the rejection of capitalism, as the core principle that the Labour Party was founded upon. The Blairites saw this as outdated rhetoric that was damaging the party’s election chances, and dumping it as “revitalising” the Labour Party. Camra, you may have noticed, has now launched its own self-styled “revitalisation project”, designed to get a consensus on where the campaign, at 45 years old, should be going next.

The question being asked is “how broad and inclusive should our campaigning be”, and the choices offered in the survey on Camra’s website, frankly, are totally dishonest. There are six, and they are that the campaign should represent

- Just drinkers of real ale, or

- Drinkers of real ale, cider and perry, or

- All beer drinkers, or

- All beer, cider and perry drinkers, or

- All pub-goers or

- All drinkers

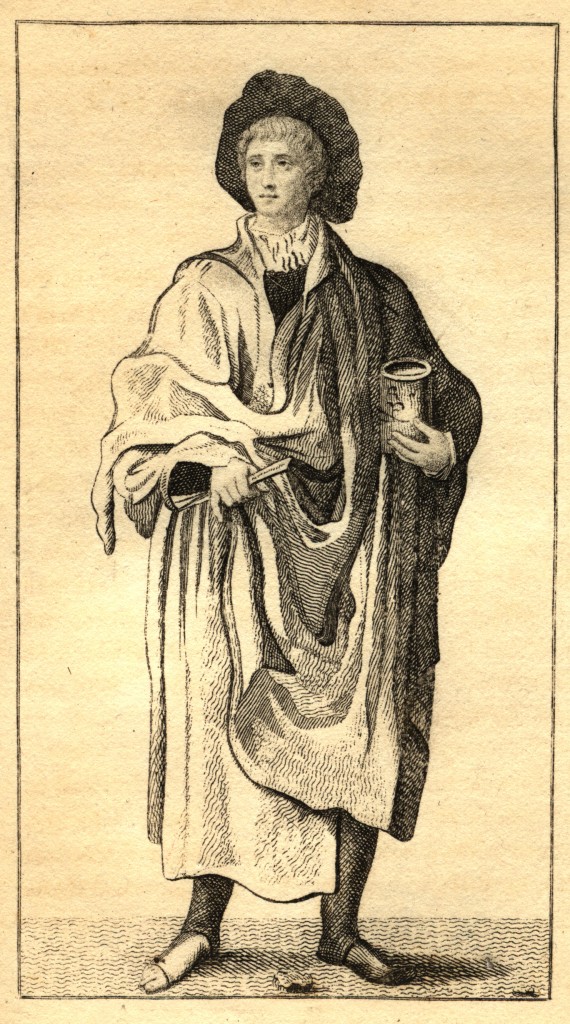

The Tudor physician Andrew Boorde (c 1490-1549), one of the earliest campaigners for real ale, who complained that while ale was ‘a naturall drynke’ for an Englishman, beer ‘doth make a man fat’.

But there isn’t a commentator that doesn’t know that four out of six of those choices are irrelevant nonsense, and the only real question Camra is asking is, “Look, are we finally going to ditch Clause Four start supporting craft keg as well as cask ale or not?”

Now, I’m aware that the support for cider and perry is controversial among some sections of Camra activists, and there are even some who question Camra’s pub campaigns, but it’s dishonesty through omission to stick those issues in there as if they were really a meaningful part of the debate about Camra’s future, and a disservice to the overwhelming majority of Camra’s membership not to make it clearer what this is really all about. In the 16-page document mailed to all Camra members about the “Revitalisation Project”, reference is made to Camra’s equivalent of Clause Four, that definition of “real ale” adopted in 1973, two years after the campaign was founded by four men who knew nothing, at that time about the technicalities of beer, only that they didn’t like the big-brand keg variety, which definition insists that the only sort of beer worth drinking is “matured by secondary fermentation in the container from which it is dispensed” and is “served without the use of extaneous carbon dioxide”. The document doesn’t, of course, point out that this definition is nonsense: the so-called “secondary fermentation” is merely a continuation of the original fermentation (you only get a true “secondary fermentation” if Bretanomyces or similar organisms kick in after Saccharomyces has finished). The subject of “craft keg” is mentioned in just one paragraph. But the, at a rough stab, 8,000 or so passionately active members of Camra know craft keg is the enormous elephant in the saloon bar that the debate is actually centred on. Many of the 170,000 other members who remain on the books more out of direct debit inertia than any enormous dedication to the cause of promoting cask ale may not grasp the true intent of this set of choices, which has clearly been presented in a way it is hoped will not antagonise the, at a rough stab, 4,000 or 5,000 passionately active members of Camra who would rather slash their throats with the shards of a broken Nonic pint glass than admit any merit at all in the craft keg movement, and who continue to fetishise a 43-year-old technically dubious idea of what good beer ought to be in the face of massive changes in the types of beer now available that go far beyond what Camra’s founding fathers, who knew only mild, bitter, stout and lager, would have thought possible.

If Camra remains purely a campaign for “real ale” as defined in the early 1970s, it will lose its relevance just the way its ineffectual predecessor the Society for the Preservation of Beers from the Wood did (not that the SPBW ever had much relevance anyway). It never seems to come up in the debate about Camra’s future, but not only is the British beer scene today totally different from that of 45 years ago, so too are the beer drinkers. More than 80 per cent of pubgoers around when Camra started are now dead. To drink legally in a pub when Camra was founded, you had to have been born no later than 1953. That makes you 63 this year. Today’s latest cadre of pub goers was born in 1998, and are very probably the granddaughters and grandsons of Camra’s first members. Fewer than one in five pub drinkers today drank in pubs before Camra was around. More than half of today’s pub drinkers were not yet born when Camra held its first meetings. They know no other world except one where cask beer is widely available and exciting new styles of beer far removed from cask ale in flavour and delivery seem to arrive every month.

Camra was founded initially to respond to a very specific set of problems caused by the big brewers who dominated the British beer market becoming completely product-oriented at the expense of the customer, and threatening the availability of the sort of tasty beers a strong minority of customers still wanted to consume. At the time Camra was founded, it was necessary to defend a narrow definition of good beer that was in danger of disappearing. It is no longer the case that cask ale is in danger: but it is still true that beer in general, and British pub culture, need promoting and defending, against ill-willed health fascists, marketing moronicity and badly briefed politicians.

It is also a fact that the 52 per cent of pub goers who are under the age of 45 have been exposed most or all of their pub-going lives to new styles of beers, notable American “craft” beers, in bottle and keg, that never existed when Camra was founded and which undeniably delivering a terrific and hugely appreciated taste experience – and one that cask ale brewers need to accept as a legitimate challenge. It will do the greater campaign for beer no good if Camra tries to insist that the very best craft keg beers are still no worthier of notice than the mass-produced mass-market keg beers that arrived in the 1960s, because fans of craft keg beer know they are drinking a product made with care and they enjoy greatly what it delivers. It would be much better for Camra to be able to say to craft keg drinkers, who are a growing part of the beer drinking community, “yes what you drink is great, we appreciate it too – have you tried cask ale, when well-kept it’s even better” than for it to continue to say to craft keg drinkers, as it effectively does at the moment: “You don’t want to drink that, it’s no better than Watney’s Red Barrel,” something they know isn’t true, even if they weren’t born when Red Barrel disappeared.

What will happen in the Clause Four Revitalisation debate? The 8,000 will speak loudly, the 4,000 loudest of all, and of the 170,000 I expect more than 95 per cent of them to remain silent: if Camra gets more than 15,000 to 16,000 responses, online or in the post, to its survey, I’d be very surprised (though I see it’s already claiming “almost 10,000” responses online), and I’d also expect the 50 or so “revitalisation consultation events” being held around the country to be dominated by members of the 8,000. At the end of all that, the men and women behind the “Revitalisation Consultation” have been politically astute enough not to commit themselves to actually taking any notice at all of what the surveys or the meetings tell them about the way Camra’s membership wants to see the campaign go: all that will happen is “the development and presentation of a formal proposal for consideration by members at the Members’ Weekend in Eastbourne in 2017”. (A quick appreciative nod here to the clever title of the consultation – “Campaign for the Revitalisation of Ale” was, of course, Camra’s original name until 1973 – and the choice of Michael Hardman, one of Camra’s four founders, to head the Revitalisation Project.)

At which point you can expect something less like the special Labour Party conference on the party’s constitution in London in April 1995 that saw Clause Four axed comparatively easily and more in line with the second congress of the Russian Social Democrat Labour Party in 1903, also in London, which saw a lasting split between Lenin and his hard-line Bolsheviks and the ultimately more conciliatory Mensheviks. Do I think that if the “Revitalisation Consultation” puts forward changes to Camra’s aims that are seen as embracing “craft keg”, there could be a split in the campaign, with the hard-line “anti-keggers” leaving to form “Real Camra”? Knowing some of those hard-liners, yes I do, and I think they could easily take two or three thousand activists with them.

On the other hand – and I speak as someone who will have been a member of Camra for 40 years next year – I doubt that more than a handful of the splitters will be under 60, and despite all that they have certainly contributed through their activism over the decades, Camra will probably be revitalised by their going, by becoming an organisation fit for a 21st century purpose, and not a 1970s one.